Everyone is a Staff Engineer Now

AI has made certain skills obsolete

Engineer’s Codex is a newsletter about real-world engineering. I know I haven’t posted in a while! The last issue was How to Write “Garbage Code” (by Linus Torvalds).

Claude Code and other coding agents this year have taken a massive leap in skill and ability. As a result, the nature of work for engineering has changed drastically.

When execution becomes cheap, the bottleneck moves elsewhere. Skills that once distinguished senior and staff+ engineers, such as architectural judgment, context management, and system-level thinking, are increasingly moving “up” the stack and are becoming expected earlier in an engineer’s career.

Historically, individual contributors split their time between implementation and higher-level work like planning and design. As agents take on more of the implementation, the engineer’s role shifts toward planning, architecting, reviewing, and deciding how to best utilize and steer these systems. This is similar to how search didn’t eliminate thinking, but rewarded people who learned how to search well as Google matured.

Writing code was never the hard part. Knowing what code to write, where to put that code, and how to design it was harder.

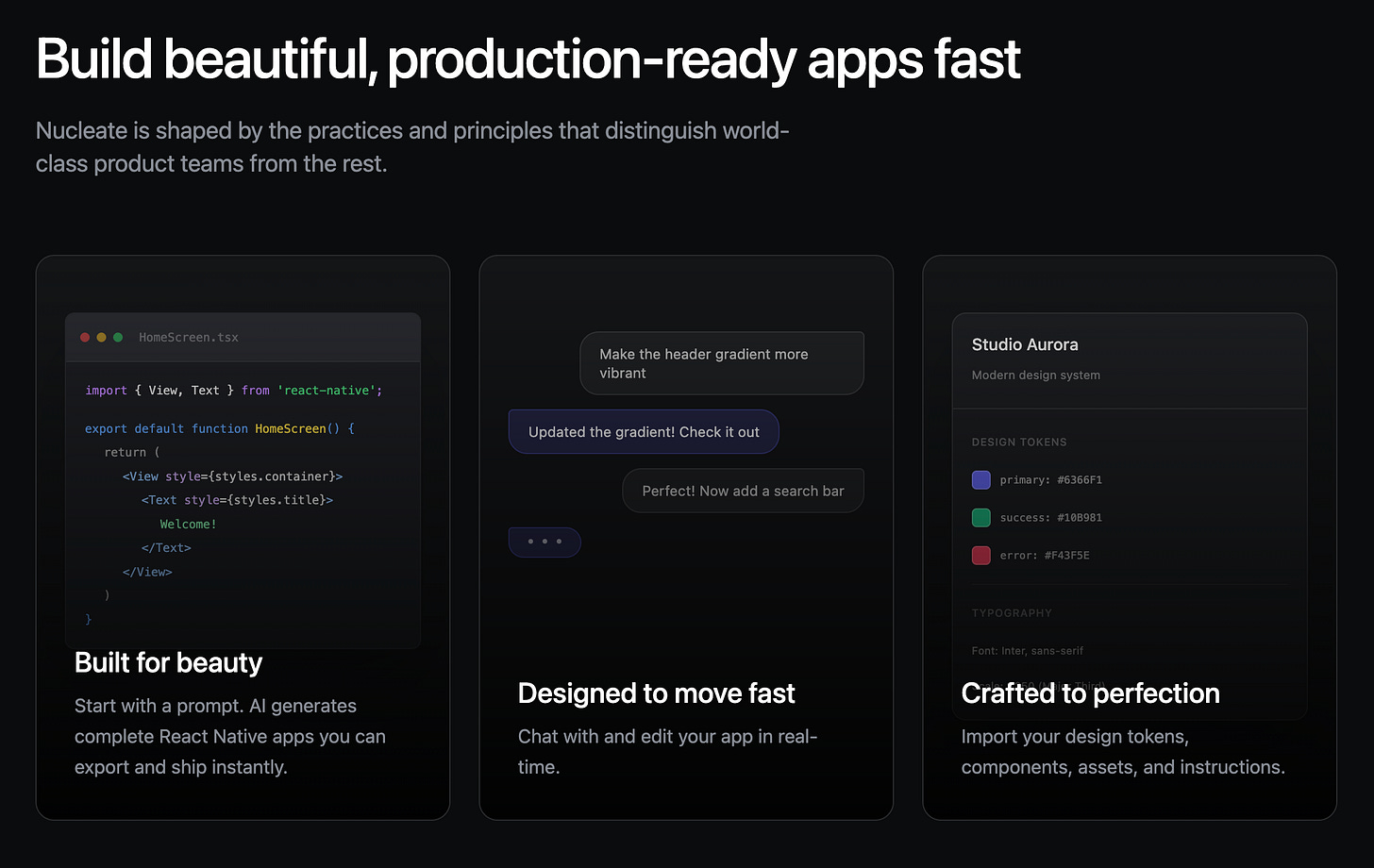

Introducing Nucleate (Featured)

Nucleate is a platform to prototype, build, and ship beautiful mobile apps with AI.

Past just coding with AI, it can integrate with your design tokens, be used as a Expo Snack replacement, and be used to generate different variants of screens.

You can use code ENGCODEX for 50% off your first month. The team is rapidly shipping updates with backend + Supabase integration, Git integrations, Claude Code subscription usage, and more coming down the pipeline this month.

Maintaining context across multiple domain and projects

When I first worked with any technical L7+ at FAANG, I was always surprised at how much knowledge they had of the stack of a huge product. They were deep in the details of how the product was built, yet still spent most of their time doing high-level architecting. The skill they had here was being able to maintain rich context across multiple domains and projects.

A senior staff engineer generally designs architectures, reviews docs and code, and generally doesn’t write as much code, as that’s delegated to junior and senior engineers. Now, AI becomes the junior engineer.

Reading code is harder than writing it, mostly because writing code fills in the “understanding” gap that reading doesn’t do as well. It’s the same reason students are recommended to write down notes rather than just read the textbook, as writing things down commits things to memory in a different way.

Engineers who can understand system context and also add to that understanding without having to write code themselves will thrive.

Consider an agent tasked with refactoring a backend service to simplify its data model. The change is clean, tests pass, and performance even improves.

What the agent doesn’t know is that another service relies on a subtle ordering guarantee in the original implementation. One that was never formally documented because it lived in shared team knowledge. After the refactor, everything still works in isolation, but downstream systems begin failing under load.

Nothing in the diff looks obviously wrong. Only someone holding context across services would recognize that a “correct” change violated an implicit contract. Yes, this is partly a human problem. But we live in a human world.

The engineer now needs to understand how components interact, track constraints across domains, and notice when a “correct” change has subtle side effects.

Maintaining focus in an asynchronous workflow

With AI agents becoming more and more long-running, it can be tough to maintain focus. The topic of “flow” has been talked about extensively in being important for programming. Flow is useful when working focusedly on one task at a time, constantly thinking, writing code, and reviewing. However, AI agents work autonomously and present changes to you at the end. It doesn’t make sense to constantly watch them as they work, leading to issues maintaining focus.

An agent may take 5 minutes to complete a task, which is enough to check your phone, email, and lose 10+ minutes to distracted tasks. Getting back into gear is contextually expensive, and thus, a real productivity decrease.

Strong engineers will need new habits:

• batching agent requests,

• planning follow-up work in advance,

• treating agent runtime as intentional gaps, not distractions.

Managing attention is already tough enough outside of work, with distractions like social media everywhere, but now it’s part of the job.

Being able to plan and steer AI agents effectively

As agents get better, being able to steer them is more and more important.

It’s generally accepted that the best way to find confidence in agentic programming is to have it generate a plan first, where you review it and update the plan as needed before implementation starts.

Part of being efficient is making this planning stage more efficient, and ideally, parallelizing multiple tasks at once where necessary. Another part of it is figuring out how to steer an agent correctly in the context you’re in. Building a new feature versus updating existing production infrastructure will require drastically different approaches.

As agents improve, the bottleneck isn’t execution speed. It’s clarity of intent. Engineers who can break work into parallelizable tasks and define clean boundaries will multiply their output.

This is also personal to everyone and requires you to understand how you work. Do you prefer planning extensively and using subagents for implementation? Do you prefer getting a prototype out first, then reviewing the code and doing a cleanup after?

Each person’s way of steering and working with AI is personal, and figuring out your own style is important to working effectively with AI.

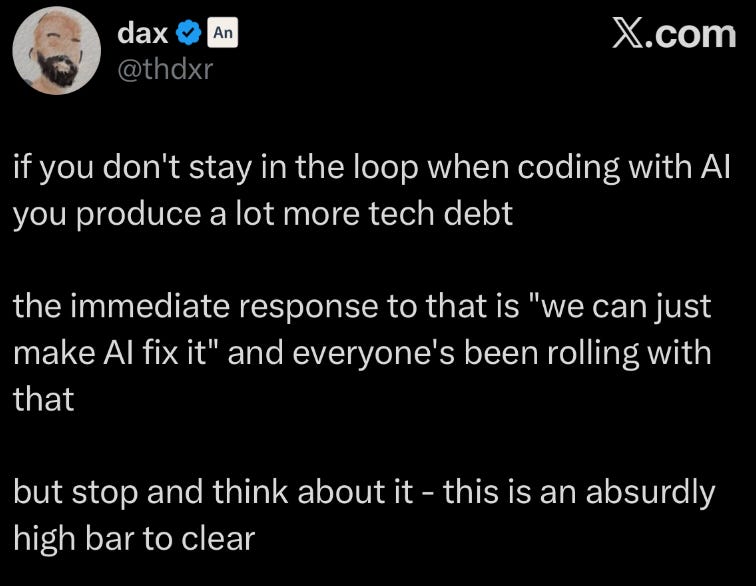

Reviewing and reading code, over writing it

Reviewing and reading code is already a hard skill that takes practice to learn. Holding the model of the previous state of a system and the proposed state of a system through reading a PR isn’t easy. AI can make this easier by writing summaries, READMEs, and other plain language to explain its work - but it’s not always aware of side effects and subtle risks like humans are.

As code generation gets cheaper, reviewing becomes more expensive. Thus, reading and reviewing code is more important than ever.

It helps that AI can help review code - but it’s best if you act as the main line of defense and use AI as a safety net.

Engineering is moving up the stack

The shift is clear: engineering work is moving up the stack. Each new model release feels like a new unlock. The skills that once separated senior engineers from junior ones, such as architectural thinking, context management, effective delegation, will now become baseline requirements.

Junior engineers now operate at what used to be senior-level abstraction. Senior engineers architect at scale previously only accessible to staff engineers.

The engineers who will thrive aren’t necessarily the ones who can prompt AI best, but the ones who can manage their own contexts the best.

Start by examining your own workflow. When do you reach for AI? When do you context-switch? Where do you lose focus? Your answers will reveal where to build new habits.

The tooling will keep improving. Your working style needs to improve with it.

The truth is that most coders are not engineers, even a lot of staff and ctos out there.

They don’t understand how errors compound, they have no idea of statistical quality control, that while not directly usable as it is in SE, it is an important discipline to understand as an engineer to develop a certain intuition.

part of the problem is that the academic world in the 90s decided that we needed more computing science and less engineering, because this was in the professional interests and in the financial interests of the Academic Industrial Complex.

I think this is a very insightful way of looking at things. My only concern is that reviewing code is very difficult, time consuming, and (at least for me) not enjoyable. How do we effectively review at the pace that AI agents are able to spit out code? How do we internalize what is actually happening instead of just giving it a surface level look and approving, saying "looks good to me". Without the work of building the system yourself, how do you create that contextual knowledge that AI might struggle with?